Inside LINQ queries[C#]

This time, we will dig deeper into LINQ queries. We will see what the C# 3.0 compiler does behind the scenes when it meets a LINQ query in code and how we can use it. Let’s take a look at a simple LINQ query:

var q =

from i in new[] {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}

where i < 5

select i.ToString("C");

The compiler handles LINQ queries in two phases. First, it translates the query into a chain of method calls. Each operator in LINQ syntax, such as where, select, … is translated respectively into the methods Where, Select, … .

var q =

new[] {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}.

Where(i => i < 5).

Select(i => i.ToString("C"));

So operator where was translated into Where method and select into Select method. As you can see, lambda expressions have also been generated and included as parameters for the method. The second phase is a discovery phase. It’s a phase of looking for the marching methods. In our example, the type “array of ints” does not have any instance method named Where, so the compiler analyzes suitable extension methods. The closest extension method with matching parameters is defined in System.Linq.Enumerable class so this is the one that will be used. Where method is a generic method, and in our case it returns an IEnumerable<int> type. The implementation of Where method is quite simple and looks like this:

public static class Enumerable

{

public static IEnumerable<TSource> Where<TSource>(this IEnumerable<TSource> source,

Func<TSource, bool> predicate)

{

foreach (var i in source)

if(predicate(i))

yield return i;

}

}

Now the compiler is looking for the Select method. Once again, type IEnumerable<int> does not contain an instance Select method, but the Enumerable class contains a matching one. Finally, our query returns type IEnumerable<string>, and the code builds successfully because all necessary methods have been found. If you are interested in how more complicated queries are translated and you are using ReSharper, hover your mouse over a LINQ query, press Alt + Enter, and choose “Convert LINQ to methods chain” option. ReSharper will automatically generate a method chain for you.

Now we can see that LINQ query is just a chain of method calls, nothing more. The real power of LINQ is the implementation of these methods. .NET Framework 3.5 gives us Enumerable, which contains about 50 methods with many different overloads, such as Where, Select, Join, GoupBy, OrderBy, etc. Almost all methods extend the IEnumerable<T> type so they can be used with all types implementing this interface, and nearly every collection of .NET Framework implementing this interface, which applies to almost all collections in the .NET Framework. I truly encourage you to familiarize yourself with those methods because they are powerful and only a few are used in simple form... where ... select LINQ queries.

Once we know how the C# compiler handles LINQ queries, we are ready to do some tricky stuff. Let’s say we would like to use the second overload of the Where method from the Enumerable class inside a LINQ query. This overload allows us to use the index of the iterated item, and the implementation looks like this:

public static class Enumerable

{

public static IEnumerable<TSource> Where<TSource>(this IEnumerable<TSource> source,

Func<TSource, int, bool> predicate)

{

int index = 0;

foreach (var i in source)

if (predicate(i, index++))

yield return i;

}

}

This means we can write a condition based on the index of the items in the queried sequence. Although we cannot extend the syntax of the LINQ query, we can extend the IEnumerable<T> type with our own Where method implementation, changing the second parameter’s type.

static class EnhancedEnumerable

{

public static IEnumerable<T> Where<T>(this IEnumerable<T> collection,

Func<T, Func<int, bool>> superPredicate)

{

int index = 0;

foreach (var item in collection)

if (superPredicate(item).Invoke(index++))

yield return item;

}

}

Now we can write a query based on the index of an item.

var q =

from i in new[] { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 }

where index =>

{

Console.WriteLine("{0}. {1}", index, i);

return (index % 2 == 0) && (i < 5);

}

select i.ToString("C");

Another interesting thing we can do with LINQ queries is to provide a set of objects describing some domain with appropriate “LINQ methods” called Where, Select, OrderBy, and so on so that we can write LINQ queries over them. This approach gives us strong control over LINQ query syntax because, during compile time, we can choose which LINQ operators we support and which we don’t. Let’s look at the example.

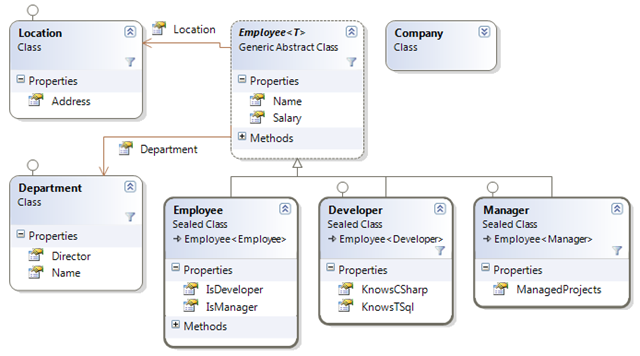

Let’s assume that we have a company, and we have a simple application storing data about our employees. The data are stored in files on the disk, and each employee is stored in a separate file. Additionally, files are grouped in folders by some common feature. For example, employees in a particular department are placed in the same folder. Let’s also assume that the main types describing our domain look like this:

Let’s start with a simple LINQ query:

Company company= new Company();

var q =

from e in company

select e.Name;

This code will not compile because the compiler cannot find the matching Select method, so we will provide it.

public class Company

{

public IEnumerable<T> Select<T>(Func<Employee, T> p) { ... }

}

It is worth mentioning that variable e in our query is an instance of the Employee type because the matched Select method takes an Employee type as the first parameter of a lambda expression. Now let’s provide support for the where operator.

var q =

from e in company

where e.Salary > 100

select e.Name;

public class Company

{

public Employee Where(Func<Employee, bool> p))

}

public abstract class Employee<T>

{

public IEnumerable<T2> Select<T2>(Func<T, T2> p) { ... }

}

public sealed class Employee : Employee<Employee> { }

As you can see this is a very powerful mechanism that gives us the ability to provide only those operators that are supported in our “query language”. We could say it is an alternative mechanism to writing a custom LINQ provider when we want to integrate LINQ queries with our specific domain. LINQ provider is much more flexible during the process of analyzing and executing queries, but this approach has one essential feature. We can choose which operators we provide and what parameters the particular operator can take. Our query is validated at compile time, which means that if we don’t support, for instance, the sort operator and some query contains that operator, compilation will fail with the error “SortBy method can not be found”. When writing a custom LINQ provider, we have to validate the LINQ query at runtime ourselves. To make this clear, look at the following query.

var q =

from Manager m in company

select m.ManagedProjects;

// this query is translated into: q = company.Cast<Manager>().Select(m => m.ManagedProjects);

public class Company

{

public T Cast<T>() where T : ICast { ... }

}

public interface ICast

{ }

public sealed class Developer : Employee<Developer>, ICast { }

public sealed class Manager : Employee<Manager>, ICast { }

We provide Cast operator for the Company type, so we can use Developer or Manager type in from clause (if fact, each type implementing ICast). Please notice that the type of variable m is Manager, not Employee, in our query. The next query will show an even more interesting feature.

var q =

from e in company

where e.Salary > 100

where e.IsManager

where e.ManagedProjects > 1

select new { e.Name, e.ManagedProjects };

public sealed class Employee

{

public Manager IsManager { get { return null; } }

public Manager Where(Func<Employee, Manager> p) { ... }

}

Here, the type of variable e in the first part of the query is Employee, but after the line “where e.IsManager”, the type of e is Manager. As we saw, we may provide support for any subset of LINQ operators, but that’s not all. We can also provide the particular operator only for a specified type, for example, “only managers can be sorted” or “we can group employees only by Department or Localization”:

var q =

from Manager m in company

orderby m.ManagedProjects descending, m.Name

select new { m.Name, m.ManagedProjects };

// q = company.Cast<Manager>().

// OrderByDescending(m => m.ManagedProjects).ThenBy(m => m.Name).

// Select(m => new {m.Name, m.ManagedProjects});

public sealed class Manager

{

public Manager OrderBy<T>(Func<Manager, T> p) { ... }

public Manager OrderByDescending<T>(Func<Manager, T> p) { ... }

public Manager ThenBy<T>(Func<Manager, T> p) { ... }

public Manager ThenByDescending<T>(Func<Manager, T> p) { ... }

}

var q =

from Developer e in company

group e by e.Location;

// q = company.Cast<Developer>().GroupBy(e => e.Location);

public abstract class Employee<T>

{

public Location Location { get; protected set; }

public Department Department { get; protected set; }

public IEnumerable<Group<Location,T>> GroupBy(Func<T, Location> p) { ... }

public IEnumerable<Group<Department, T>> GroupBy(Func<T, Department> p) { ... }

}

public class Group<TKey, T>

{

public TKey Key { get; private set;}

public IEnumerable<T> Items { get; private set;}

internal Group(TKey key, IEnumerable<T> items)

{

Key = key;

Items = items;

}

}

Finally, I’d like to show you how smart the C# 3.0 compiler is. When the compiler meets a LINQ query with a simple select operator like this:

var q =

from i in new[] {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}

where i < 5

select i;

The small optimization takes place. Because our query after translation looks like this:

var q =

new[] {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}.

Where(i => i < 5).

Select(i => i);

so probably calling Select method does not change anything (converting i into i), so this call is not generated, and the final code looks like this:

var q =

new[] {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}.

Where(i => i < 5);

Of course, in this particular case (LINQ to objects), it is true. But if we provide our own Select method returning DateTime type and place the EnhancedEnumerable class “closer” to the above query (for instance, in the same namespace), then our method will be used instead of the standard LINQ operator (System.Linq.Enumerable.Where).

static class EnhancedEnumerable

{

public static DateTime Select<TSource, TResult>(this IEnumerable<TSource> source,

Func<TSource, TResult> predicate)

{

return DateTime.Now;

}

}

In such a case, will the optimization take place? Yes, it will. The optimization is performed in the first phase of query translation when we don’t know yet which Select method will be used or if any exists. There are more such optimizations, so we should be careful when writing more advanced queries.

Treat this post as a prerequisite for the next few posts, where we will be talking more about LINQ internals.

You can download the whole “queryable” solution with classes, such as Company, Employee, Developer, and so on, from here.